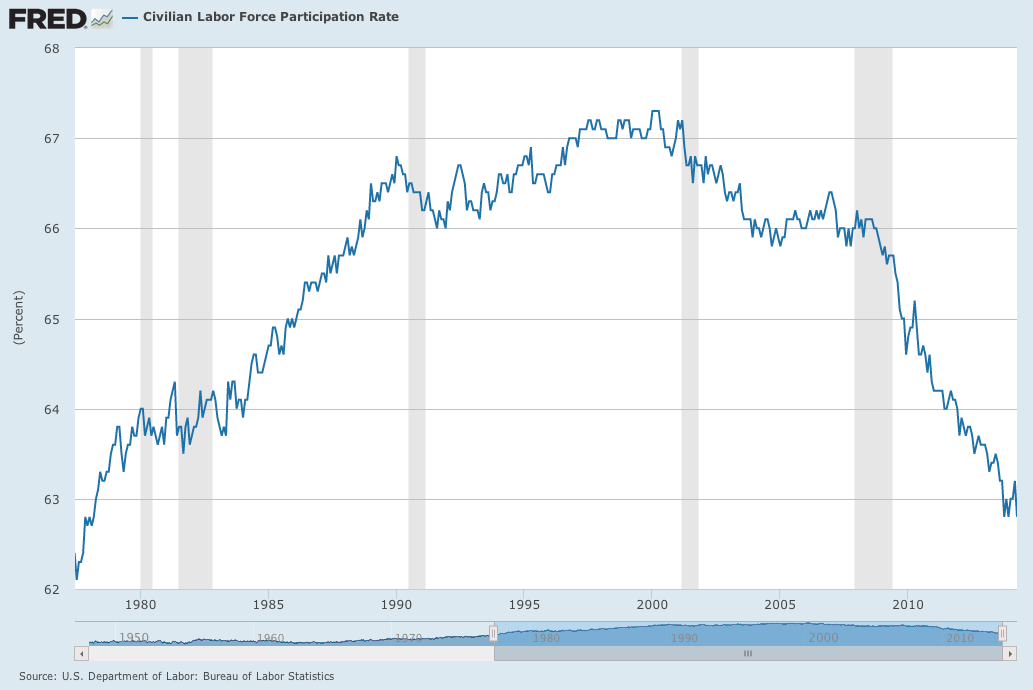

Two charts say a lot about civilian labor participation rates. One from the St. Louis Fed (FRED) showing civilian labor participation over the last 36 years:

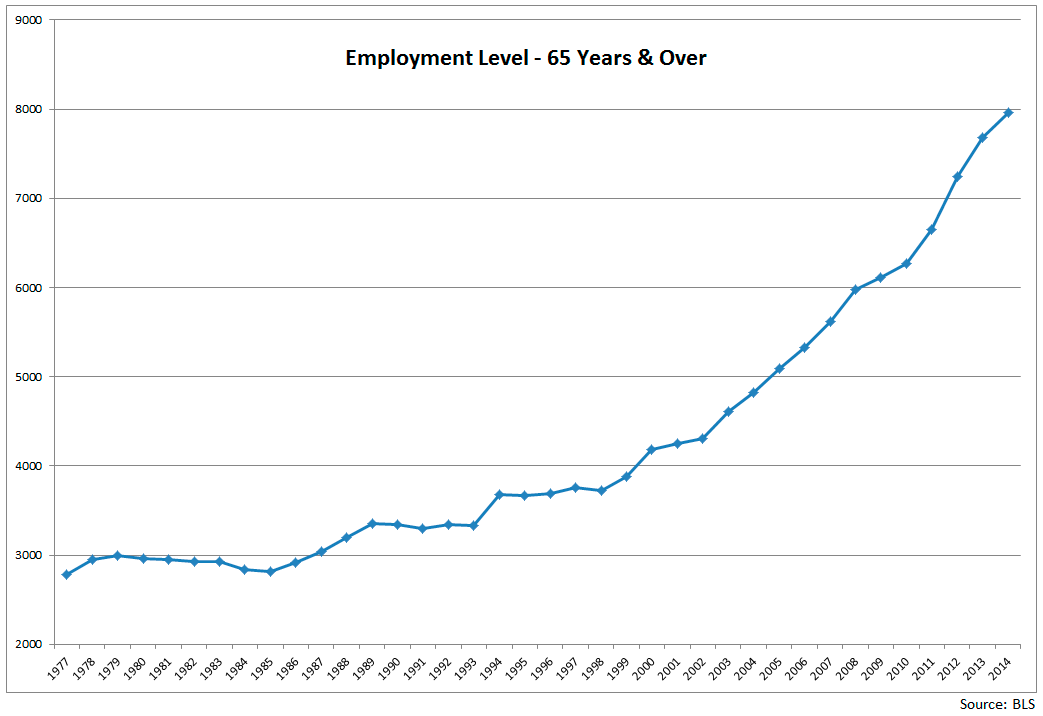

The other, from the BLS showing a labor trend over the same time span for those 65 and over:

What are the long-term implications for this? We certainly cannot draw a conclusion based on two charts alone, but this is a recurring theme as we consider retirement (whether it be a pension, Social Security, or any other form) as well as employment among a very large segment of the population made up of Millennial’s. There is a lot of discussion of the number and percentage of Americans 65. The projections in the next 20 years are alarming. A recent post on Five Thirty Eight observes the following:

The recession may have delayed the inevitable for a time. The financial crisis wiped away billions in retirement savings, forcing many Americans to work longer than planned. But the stock market has since rebounded, and there are signs that more Americans are at last feeling confident enough to leave the workforce. The labor force participation rate for older Americans — the share of those 55 and older who are working or actively looking for work — has fallen over the past year after rising through the recession and early years of the recovery. Roughly 17 percent of baby boomers now report that they are retired, up from 10 percent in 2010.

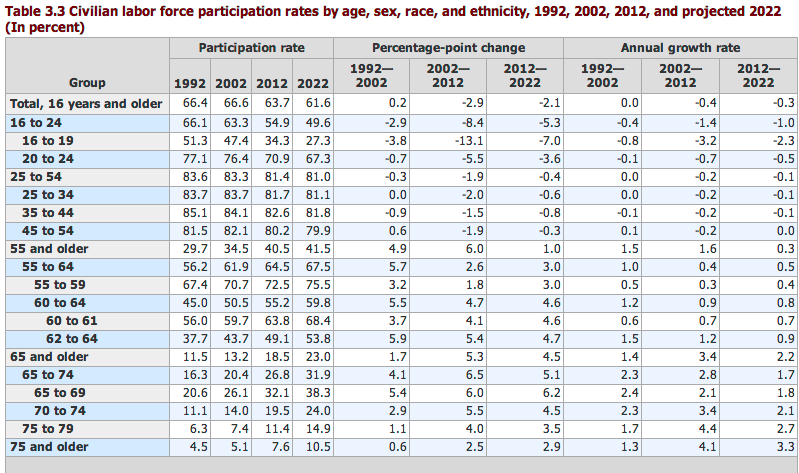

While I agree that some temporarily prolonged entering retirement due to market, the problem with this conclusion on its own is that the trend of increased participation rate among this age group predates this statistic by about 30 years. What’s more, this trend not only predates the statistic, but by an astonishing rate of increase in the last fifteen or so years. I do not believe this trend is the result of simply living longer and certainly not the result of the average American’s job satisfaction. A BLS table for all age groups covering twenty years from 1992-2012 further punctuates this point: steady increases in participation rates as a whole begin with those 55 and older. This really ramps up among those in the retirement age ranks:

I think it is also difficult to draw clear conclusions of what this all means because we do not have a precedent in our country or our labor force to compare this to. Oddly enough, many of those in the higher participation categories have spent much of their careers in what might be considered the golden age of pensions and retirement options. And yet, participation rates from that age group have continued to increase (unless that trend is now reversed permanently based on the series data from the current year). What is required is that we rethink work, careers and entrepreneurship for all age groups. Sixteen years ago Peter Drucker said, “Demographics are the single most important factor that nobody pays attention to, and when they do pay attention, they miss the point.” Speaking of the coming avalanche of retired [age] knowledge workers that he and a few others seem to see very clearly:

Retired knowledge workers with marketable skills are going back to work–but not full-time, not to an office, not to commuting. Working part-time beats sitting at home and moaning or playing bridge all day. The bottom line is that if you go forward to 2010, when baby-boomers will be retiring, increasingly fewer will be blue-collar workers. So most will be able to work well into their 70s.

Three years later (2001) in The Economist, he went on to make the point that while we cannot predict what a new economy is exactly or what it will look like, but that radical and essential sociological shifts are here and now. Perhaps we should have paid more attention to this thirteen years ago. He also pointed out as I stated earlier, the difficulty is that we have little to compare it to in this country. He saw it as plain as day:

Within 20 or 25 years, however, perhaps as many as half the people who work for an organisation will not be employed by it, certainly not on a full-time basis. This will be especially true for older people. New ways of working with people at arm’s length will increasingly become the central managerial issue of employing organisations, and not just of businesses.

Again, adding to this trend, the last six years of our economy has had found implications on what it means for younger people looking for jobs. There is also a remarkable struggle among those of an older age bracket dealing with the challenges of mismatched skill sets. Combine this with the natural order of innovation and technology that now affects jobs previously untouched by technology (information based, service, clerical, etc.) and you have this whole new social order that was spoken of fifteen years ago. In spite of this, there are still tremendous opportunities. But the biggest difference is how much pressure is put on the individual to take active and aggressive steps to take charge of their own future. I think this begins with a complete rework of our perspective of what career means.