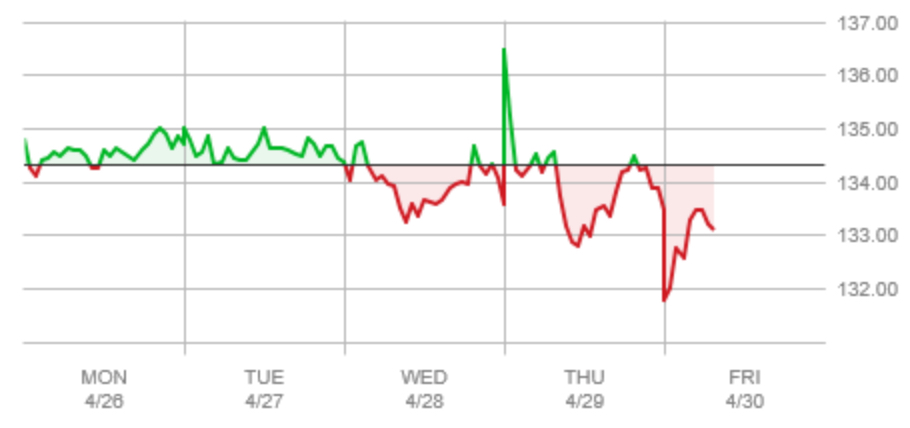

There has yet to be a decrease or contraction in month-over-month inflation – and yet the market has another record-setting day in terms of volatility. The better-than-expected (7.7 vs 8% reduction in the rate of increase) squeezed off a tape bomb:

S&P 500 makes historic leap…as investors went risk off, mostly predicated on the cratering of the cryptocurrency markets. And the unknown of the October consumer price index reading made the bulls less aggressive during the steep decline.

In what may be the biggest 1-minute green bar in the entire history of the index, it leapt nearly 110 handles, or 3%, (3,751.50-3,861) at the 8:31 a.m. mark. The stocks in the index were following suit. In retrospect, even buying at those elevated prices has been profitable. (ToS news, 11/10/2022)

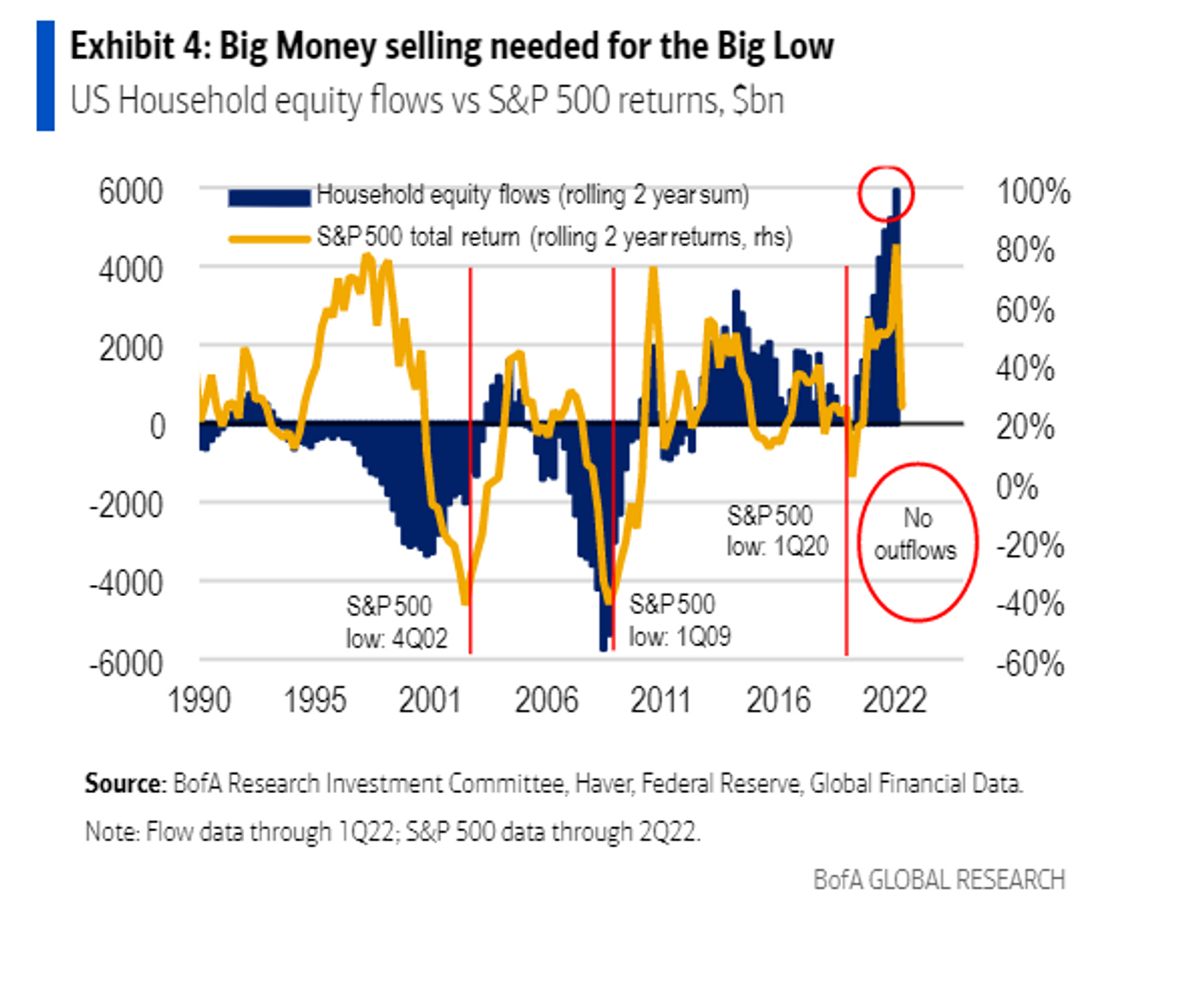

But as welcome as a slowing of increase is, the response (and following wealth effect) is largely an illusion:

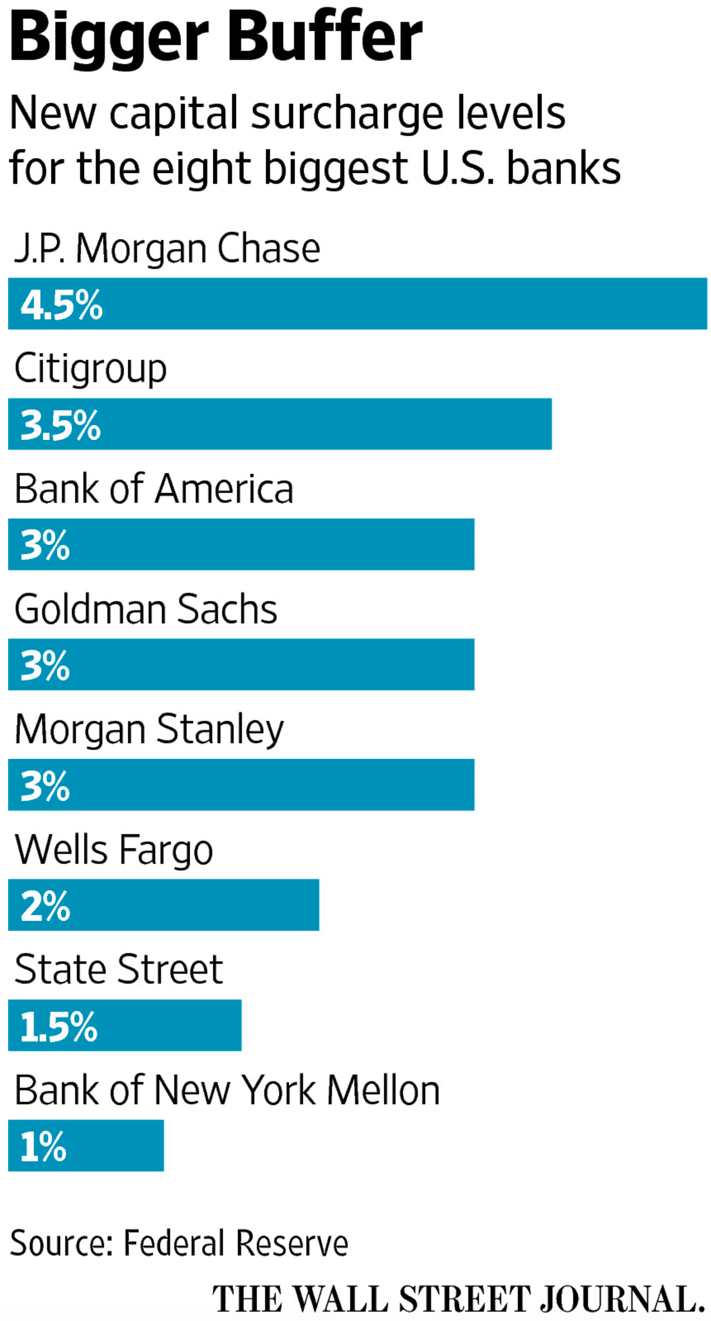

This morning’s CPI report does little to alleviate that call for further policy action. While the headline has come off peak levels, the momentum in prices remains robust, suggesting, as Fed Chairman Jerome Powell did last week, there is still a significant amount of work yet to be done.

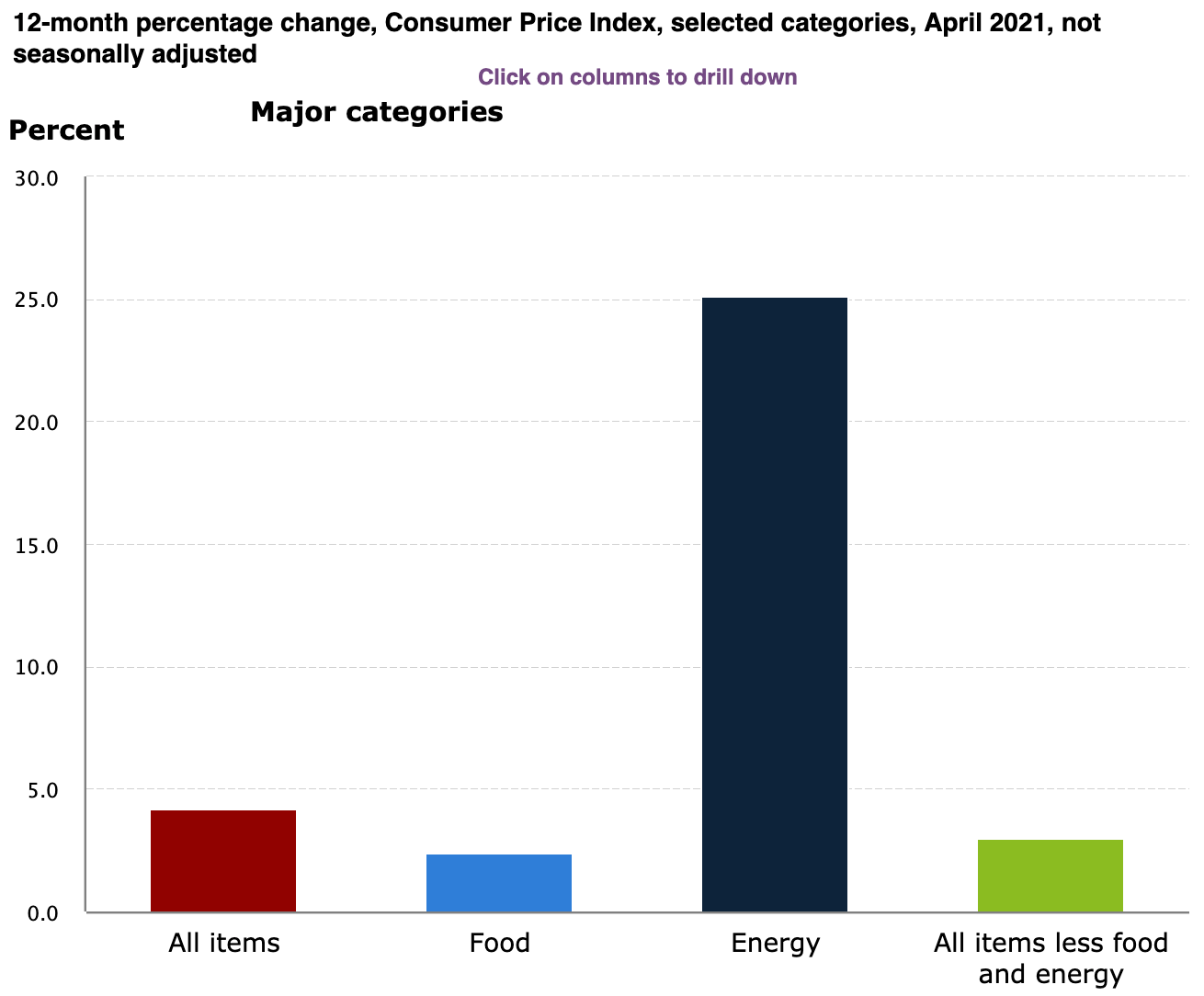

As expected, shelter and energy costs continue to be key drivers of the headline rise. While housing prices have slowed, given the multi-year deficit of supply, even with demand off peak levels and supply rising from earlier lows, there remains a sizable gap between the existing need and stockpile of housing units, providing structural support to prices. (Stifel)

Whether 50 bps is priced in or not doesn’t matter. The lack of recognition of the ongoing damage is protracting the problem – the country is still at 40-year highs in terms of cost escalations: