In a post by former United States Secretary of the Treasury, Dr. Summers writes, “curbing inflation comes first, but we can’t stop there.” In this essay, a complexity of problems are addressed, including a few strengths such as an extraordinarily strong labor market, given the negative GDP growth of the first six months of this year. All have acknowledged this odd combination where recessionary threats exist but several jobs are still seemingly available to any looking for them – this is only due in part to the strength of the overall economy, but it is a point that should be acknowledged, alongside a bizarre mixture of the post-pandemic workforce that do not appear to be returning to traditional jobs, at least at this present time.

Summers goes on to outline the “serious, interconnected problems demanding attention” regarding the following challenges (all emphases mine):

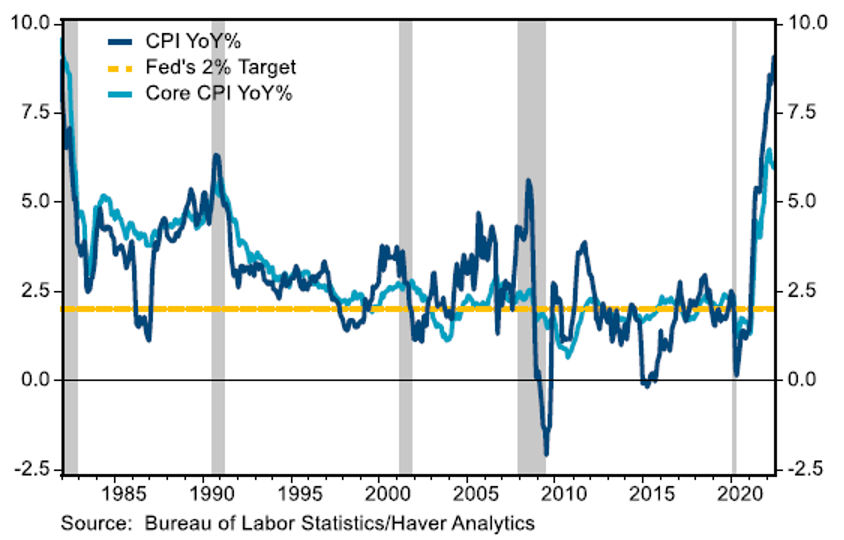

First, an economy that even progressives such as Paul Krugman recognize as overheated is operating with a core inflation rate that is close to 7 percent and is not yet declining — with the latest monthly figure exceeding the latest quarterly figure, which in turn exceeds the latest annual figure.

Second, the combination of the adverse effects of inflation and the adverse effects of necessary anti-inflation policies has prompted a consensus prediction of recession beginning in 2023. The most recent Federal Reserve projection suggesting that inflation can be brought down to 2 percent without unemployment rising above 4.4 percent is simply not plausible as a forecast.

Third, the Fed has raised interest rates in a way that markets would have thought unlikely in the extreme only a year ago. Markets are reeling from the shock, with the possibility that normal trading could break down in the Treasury bond market, an event that if unchecked would have significant ramifications for other markets.

Fourth, the global economy is everywhere challenged by rising U.S. interest rates and a dollar exchange rate at record levels against some key currencies. The fallout from the war in Ukraine has also been devastating to many economies. A weak and closing global economy hurts our exporters and markets and dangerously implicates vital national security interests.

But managing inflation not seen in four decades remains the grand central theme and cannot be overstated:

The objective of policy should be clear, at least. What is most important is that the maximum number of Americans who want to work are able to work at as high an income as possible, now and in the future. Other matters — from the level of government debt to the functioning of financial markets to business incentives to inflation — are not important for their own sakes but because of their effects over time on employment and income.

Put another way: Questions of macroeconomic policy are not about values but judgments about the ultimate effects of various actions. As Fed chair during the early 1980s, Paul Volcker famously tamed out-of-control inflation at the cost of a severe recession. But he did so not because he cared less about unemployment or worker incomes than his predecessors did but because he rightly recognized that delay in containing inflation would only mean more pain down the road.

This principle can be seen in the current labor market. Even as job openings have risen to unprecedented levels and labor shortages have empowered workers, Americans’ real incomes have declined significantly. Unless inflation comes down, workers will not see meaningful increases in their purchasing power — and many of them will continue to doubt the government’s ability to carry out basic tasks.

That’s why it’s vital that the Federal Reserve not waver. Chair Jerome H. Powell has vowed to impose sufficiently restrictive monetary policy to return inflation to within range of the Fed’s 2 percent target. The more confident that workers, businesses and markets are that the Fed will follow through on that, the less painful the process will be.

Dr. Summers goes on goes on to suggest policy measures in the out years that should not be overlooked, see the full discussion here. It is a sincere hope that Chair Powell and the other Governors will hear Dr. Summers and other voices of former Fed officials who have consistently warned for well over a year regarding the nature of cost escalations and excessive spending and liquidy. This is critically important as the capital markets continue a defiance that is likely to make things worse and prolong the solution, given the known impacts of the wealth effect – a topic that doesn’t appear to get enough attention or exploration.