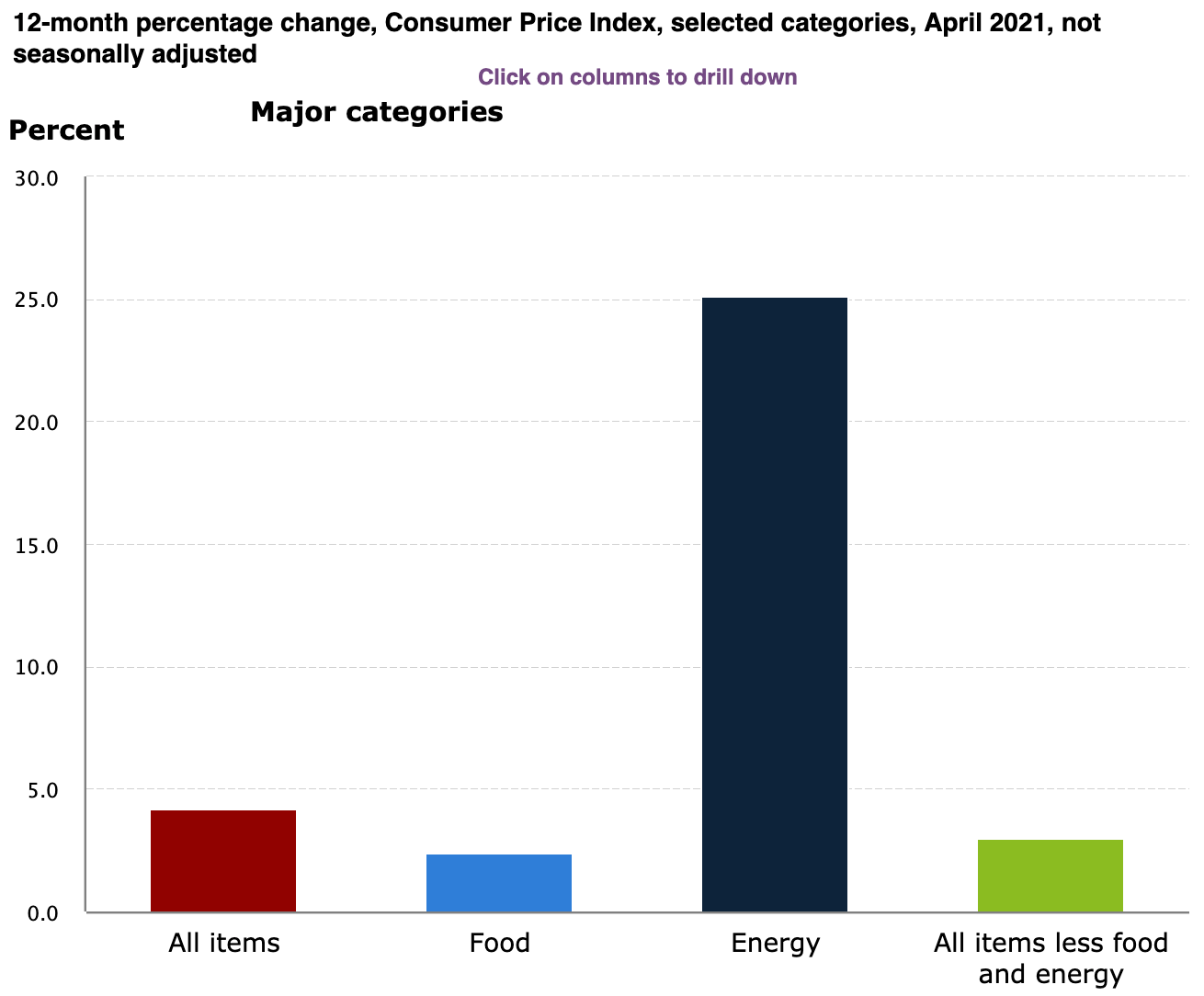

As expected, the CPI news release (April 2021) today shows significant inflation, as that has been the anecdote from almost everywhere. The surprise is just how much and how fast:

The Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) increased 0.8 percent in April on a seasonally adjusted basis after rising 0.6 percent in March, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Over the last 12 months, the all items index increased 4.2 percent before seasonal adjustment. This is the largest 12-month increase since a 4.9-percent increase for the period ending September 2008.

Pent up and bottlenecked economy

The question is why this pace of increase or does this signal long-term problems. The most immediate causes relate to the re-opening of the economy. From MarketWatch:

The pace of inflation has surged after years of languishing at unusually low levels largely due to the rapid reopening of the U.S. economy.

Businesses can’t keep up in demand, a problem exacerbated by ongoing bottlenecks in the global trading system tied to the pandemic. Computer chips are especially in short supply and that’s held up production of new autos and other manufactured goods.

Americans are also rushing to dine out, travel or go far away for vacation, activities they shied away from during the pandemic. That’s also driving up prices at popular vacation resorts and other venues where people plan to congregate.

The first two reasons are pretty straightforward, but the third reason (pent up demand) is beyond question, even if this one is the most difficult to measure as it’s anecdotal and not enirely precise but we all observe it – everywhere is packed with people looking to get out and do something, anything. But the impacts are real and tangible as seen in the BLS data:

See full interactive (and drillable detail) here.