The Bank for International Settlements released its 84th Annual Report with the first 121 pages of the 256 page document dedicated to an economic, historical and statistical overview, followed by policy driven conclusions and the prospects of our future as they forecast it. From the beginning, a clear message is stated in its press release,

Time to step out of the shadow of the crisis…A new policy compass is needed to help the global economy step out of the shadow of the Great Financial Crisis…the BIS calls for adjustments to the current policy mix and to policy frameworks with the aim of restoring sustainable and balanced economic growth.

This admonition comes from an assessment of the global market where on the one hand, there is a firming trend in a positive direction. But on the other, despite

Unusually accommodative monetary conditions, investment remains weak. Debt, both private and public, continues to rise while productivity growth has further extended its long-term downward trend. There is even talk of secular stagnation.

Where are we now?

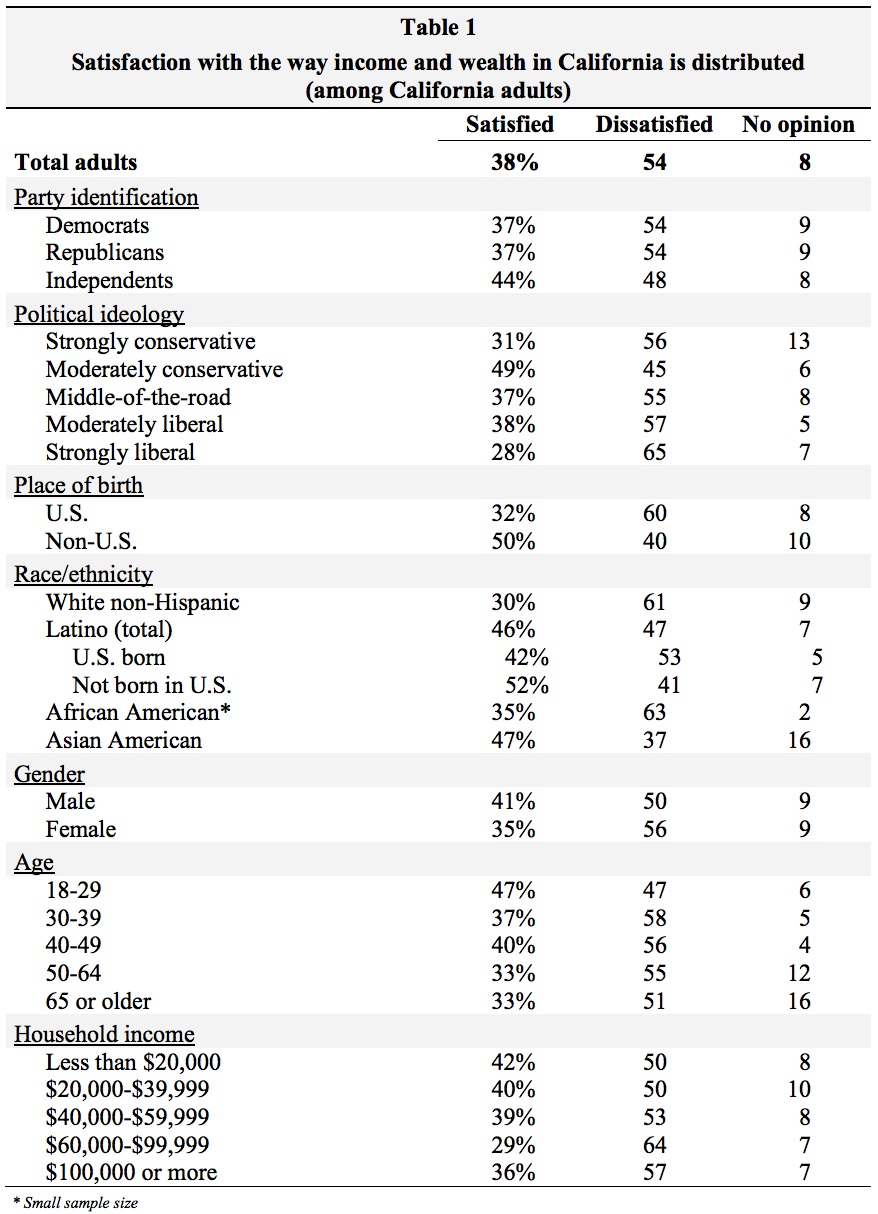

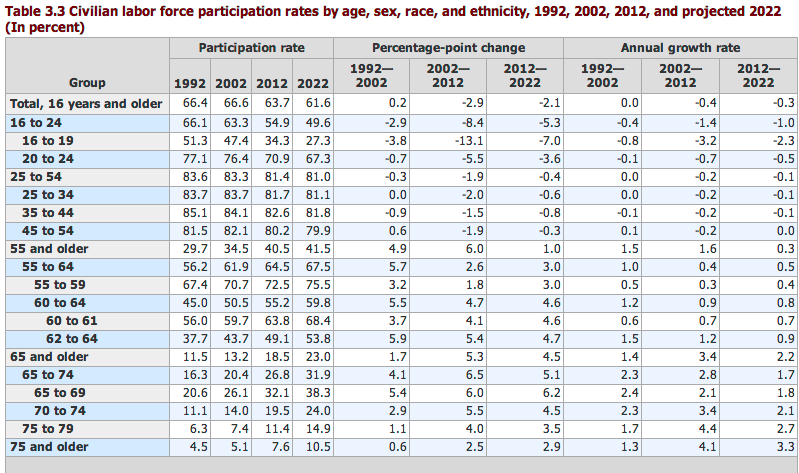

In respect to financial markets, personal balance sheets and indebtedness, the following was noted:

The financial sector’s health has improved, but scars remain. In crisis-hit economies, banks have made progress in raising capital, largely through retained earnings and new issues, under substantial market and regulatory pressure. That said, in some jurisdictions doubts linger about asset quality and how far balance sheets have been repaired. Not surprisingly, the comparative weakness of banks has supported a major expansion of corporate bond markets as an alternative source of funding. Elsewhere, in many countries less affected by the crisis and on the back of rapid credit growth, balance sheets look stronger but have started to deteriorate in some cases.

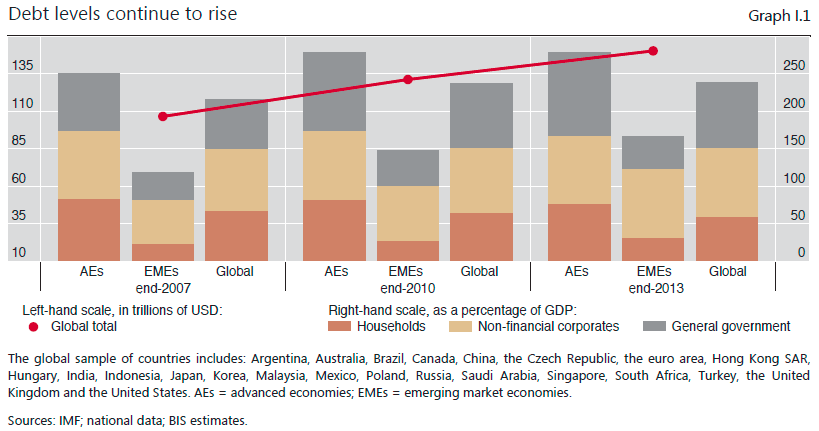

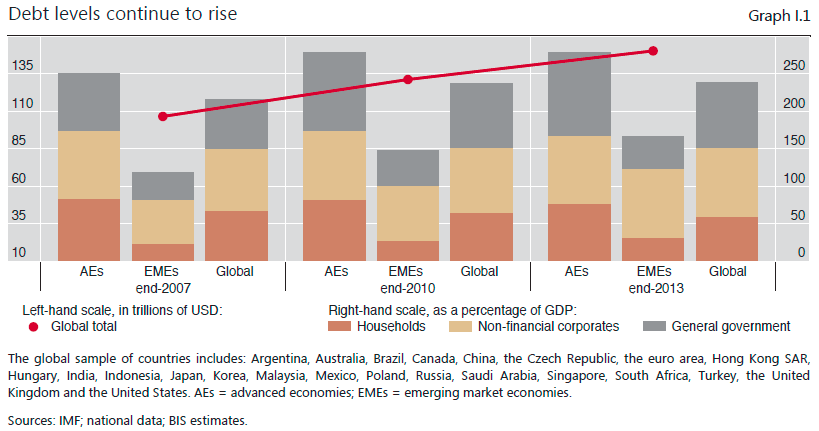

Private non-financial sector balance sheets have been profoundly affected by the crisis and pre-crisis trends. In crisis-hit economies, private sector credit expansion has been slow, but debt-to-GDP ratios generally remain high, even if they have come down in some countries. At the other end of the spectrum, several economies that escaped the crisis, particularly EMEs, have seen credit and asset price booms which have only recently started to slow. Globally, the total debt of private non-financial sectors has risen by some 30% since the crisis, pushing up its ratio to GDP (Graph I.1).

How does this compare with the U.S.?

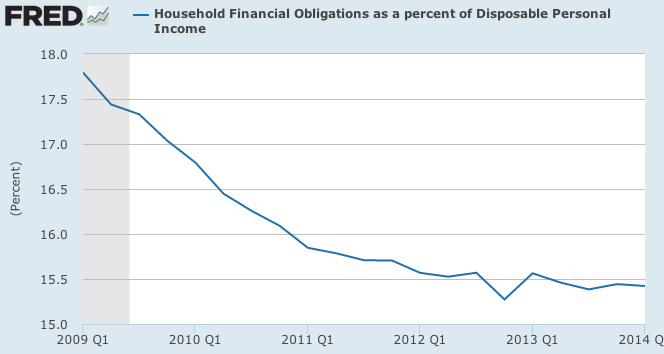

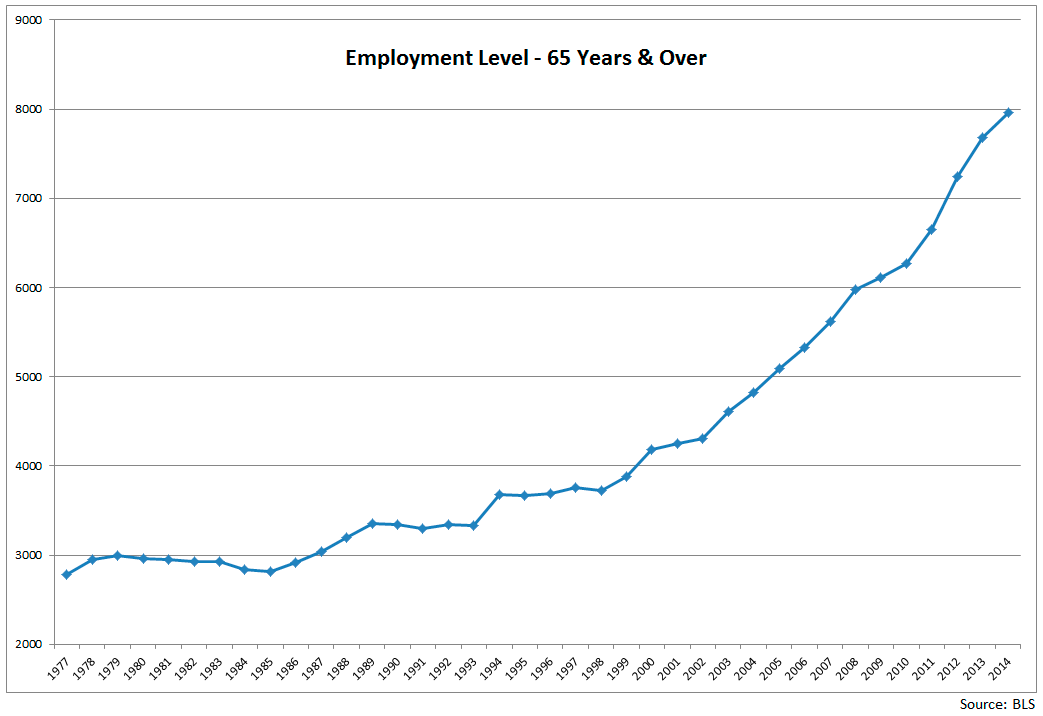

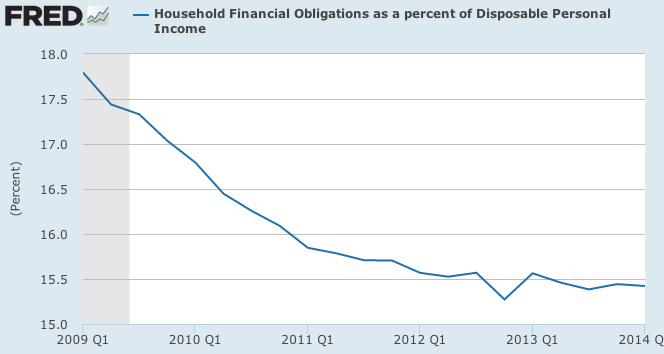

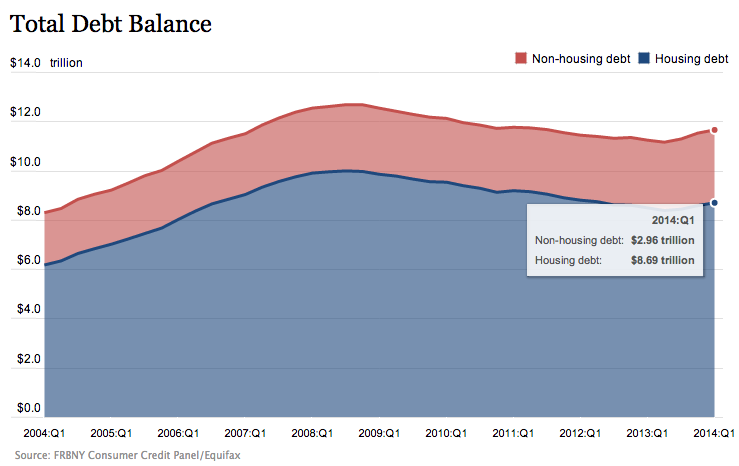

U.S. households started deleveraging at a remarkable rate beginning in Q1 2009 and continued at a steep downward pace until the end of 2013. This trend leveled off as indicated by the FRED data below:

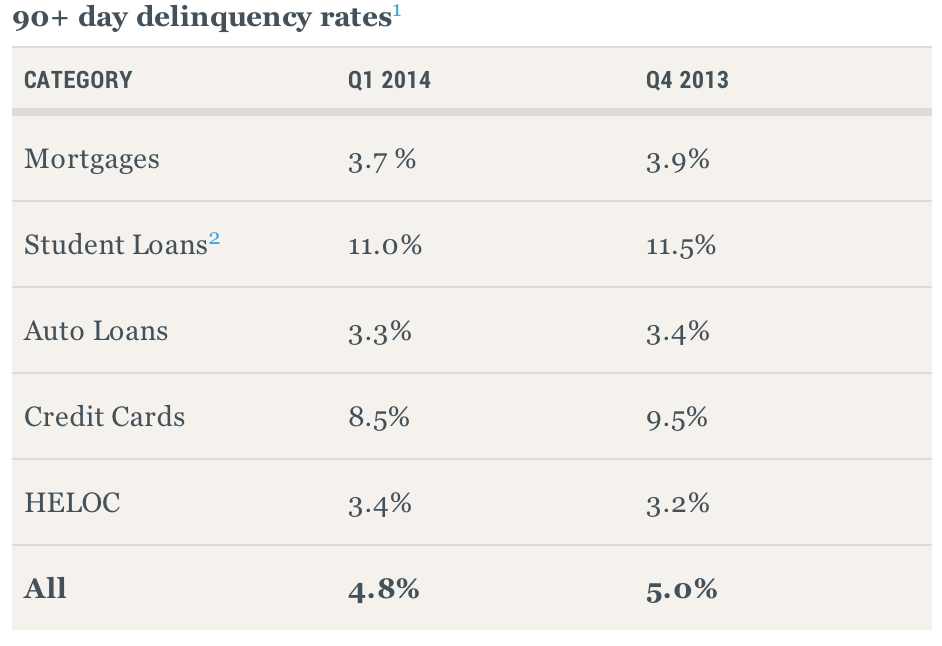

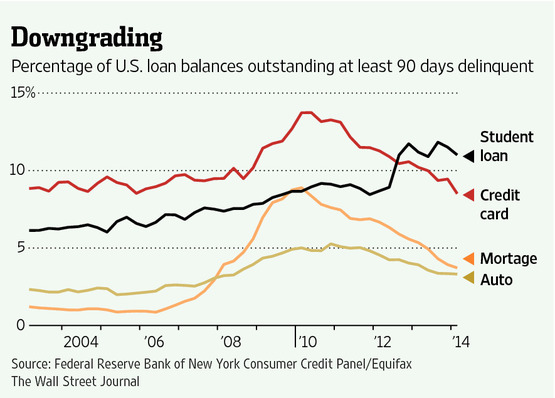

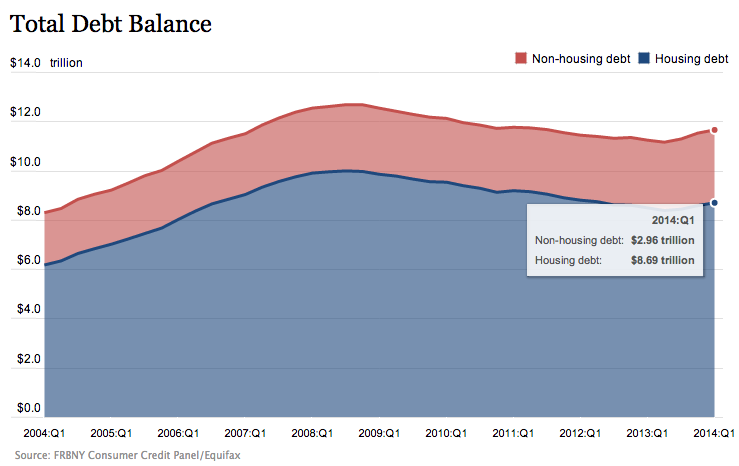

The New York Fed finds household debt has increased for three quarters with the following release from May:

In its Q1 2014 Household Debt and Credit Report, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York announced that outstanding household debt increased $129 billion from the previous quarter. The increase was led by rises in mortgage debt ($116 billion), student loan debt ($31 billion) and auto loan balances ($12 billion), slightly offset by a $27 billion declines in credit card and HELOC balances. Total household indebtedness stood at $11.65 trillion, 1.1 percent higher than the previous quarter. Overall household debt remains 8.1 percent below the peak of $12.68 trillion reached in Q3 2008. The report is based on data from the New York Fed’s Consumer Credit Panel, a nationally representative sample drawn from anonymized Equifax credit data.

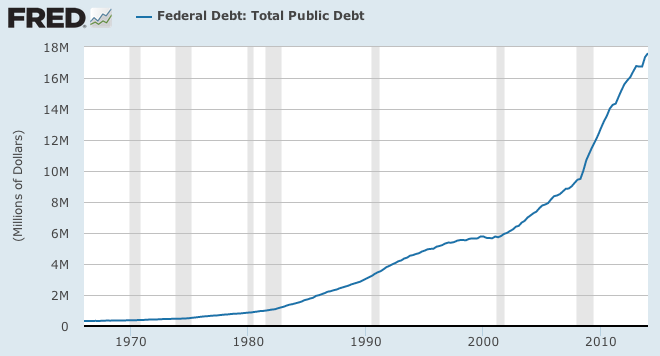

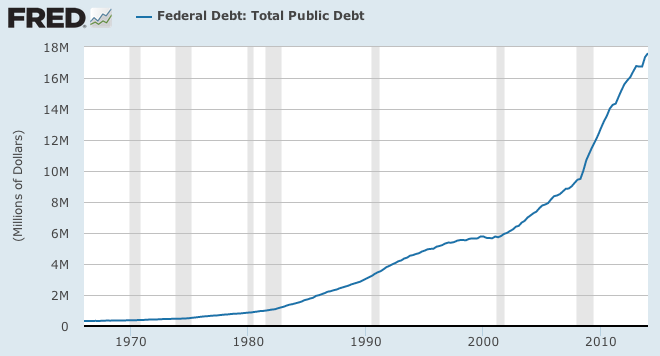

This is combined with what we already know regarding indebtedness at the Federal level, and how it ballooned in direct response to the credit crisis and crash that followed:

And this is consistent with the global findings of the BIS report.

What options are available?

What is somewhat disconcerting is the conclusion that central banks may be running out of options in the event of another recession, “particularly worrying is the limited room for maneuver in macroeconomic policy.” That’s the bad news. And within the limited scope of available options, the following cautionary tone follows the good news of recent months of stability,

The overall impression is that the global economy is healing but remains unbalanced. Growth has picked up, but long-term prospects are not that bright. Financial markets are euphoric, but progress in strengthening banks’ balance sheets has been uneven and private debt keeps growing. Macroeconomic policy has little room for manoeuvre to deal with any untoward surprises that might be sprung, including a normal recession.

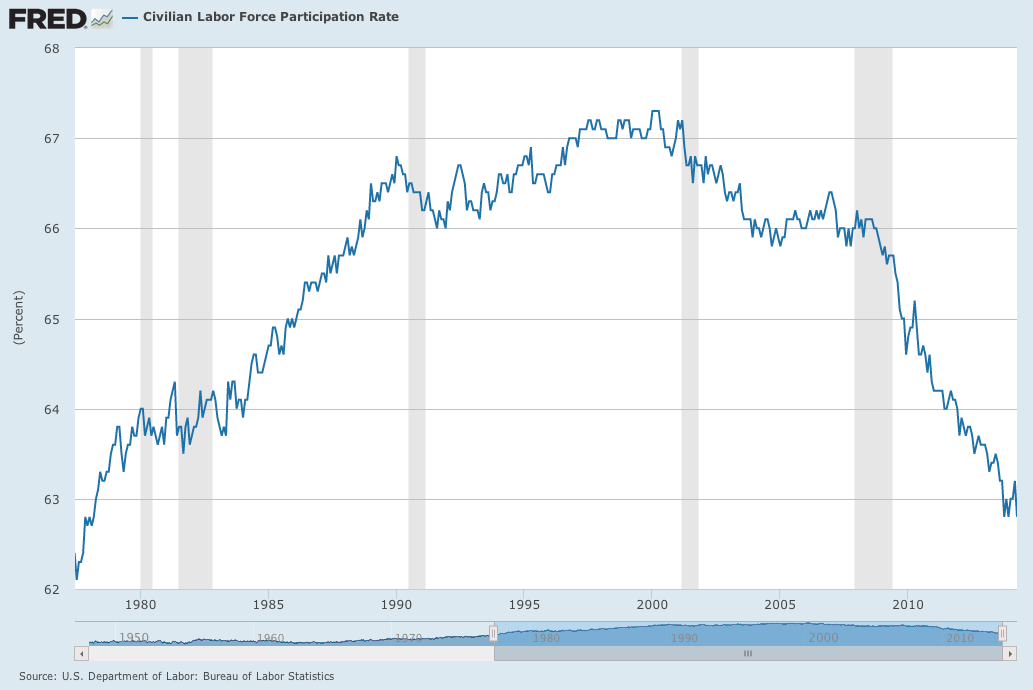

Thus the much tweeted comment along the lines of a euphoric market that is completely out of sync with economic fundamentals, sustainable growth, rational debt levels and future employment (for nations such as the U.S.).

The agonizing conclusion of limited options at the policymaker level is derived from the fact that in recent decades, there has simply been too much manipulation,

Credit and property prices soared, shrugging off a shallow recession in the early 2000s and boosting economic growth once more. Spirits ran high. There was talk of a Great Moderation – a general sense that policymakers had finally tamed the business cycle and uncovered the deepest secrets of the economy. The recession that followed shattered this illusion. As the financial boom turned to bust, a financial crisis of rare proportions erupted. Output and world trade collapsed. The ghost of the Great Depression loomed large.

The output of what followed is what is in hindsight understood as a “Balance Sheet Recession.” This is a particularly troublesome term because it sets this recession and recovery apart from other post-war recessions and recoveries in the U.S. The term is explained as follows,

The term “balance sheet recession” was probably first introduced by R. Koo, Balance Sheet Recession, John Wiley & Sons, 2003, to explain Japan’s stagnant growth after the bursting of its equity and real estate bubble in the early 1990s. [The term is used here] to indicate the contraction of output associated with a financial crisis that follows a financial boom.

The question of course is, how does this happen? It all boils down to the management of the “good times” during the run up. Debt is accumulated while expectations of a bright future are soaring. This occurs at the individual and household levels, and permeates institutions and firms all across private sector business, as well as local, regional, state and federal institutions of government. And that is exactly what happened. What follows is the bloating of asset prices that are completely disproportionate with real economic output. When it is discovered (however it occurs in the market psyche) that optimistic expectations cannot continue, scrambling occurs in the absence of liquidity in the form of fire sale of assets and thus, a priority follows of, “balance sheet repair over spending.” How long and how deep the following slump depends on any number of complexities, but what follows is a struggling economy that is attempting to regain traction in the absence of traditional lending. This means a balance sheet recession can be a very long and difficult recovery,

The empirical evidence confirms that recoveries from a financial crisis are drawn-out affairs. On average, it takes about four and a half years for (per capita) output to rise above its pre-crisis peak, or about 10 years if the Great Depression is taken into account. The recovery of employment is even slower (Reinhardt and Rogoff (2009)).

Policy and Moving Forward

It would appear that little can be done in the short term, other than endure the headwinds of modest growth, especially in the labor market. But in the long term, we can hope that a long struggle with employment may shape the future of monetary policy:

Looking ahead, the transition from extraordinary monetary ease to more normal policy settings poses a number of unprecedented challenges. It will require deft timing and skilful navigation of economic, financial and political factors, and hence it will be difficult to ensure a smooth normalisation. The prospects for a bumpy exit together with other factors suggest that the predominant risk is that central banks will find themselves behind the curve, exiting too late or too slowly.

In other words, will we be able to wean ourselves from the addiction to manipulating markets once growth returns to historic levels? “The argument urging central bank restraint focuses on inflation and the business cycle at the expense of the financial cycle, ignores the impact on sovereign fiscal positions and may well put too much faith in the powers of communication.” The conclusion is that we are at a crossroads. Our financial and banking sectors have made progress, and a significant sociological shift has occurred in terms of our attitudes toward risk and attempts at regulatory reform and implementation. See the full report here.