Last year, the U.S. Census issued an excellent report, An Aging Nation: The Older Population in

the United States – Population Estimates and Projections and as you might guess, the findings are nothing short of alarming. Why? Because the findings in the report have a number of significant implications connected with aging in general and all its added responsibilities such as health care and social security. What’s more, the very large baby boom cohort (the report uses the traditional timespan of those born from 1946-1964) has for some time represented such a significant part of the work force, but now its rotation out of the workforce is adding to the weight of what the report labels, “older population” (defined as those above 65 years of age). Combine this with the extrapolation of the older Generation X cohort in the next few decades, plus overall mortality projections showing increased life expectancies and you have a mind boggling number of people not only meeting the definition of older, but in excess of 85 years of age.

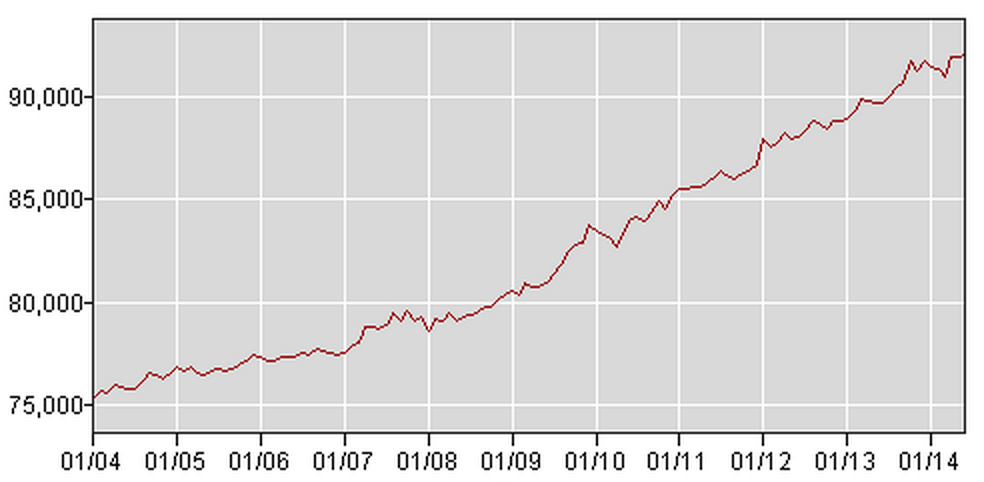

Historical Look Using an Interactive Graphic

Below is an interactive graphic from the Census Bureau that can be used in two ways. Slide the year along the bottom for a view of the population breakdown by age at a given point in time in the last ten to fifteen years. Going back fifteen years to the year 2000, you see a very large cohort in their thirties to early fifties. As you slide the year to the right (toward the present), you see the rising age, which is somewhat self-obviating given the starting point. But then as you reach the near present, you see a surprising trend of a new cohort, now in their early twenties to early thirties, representing a significant part of the population.

Implications of the Elderly

According to the projections in the Census report:

Between 2012 and 2050, the U.S. population is projected to grow from 314 million in 2012 to 400 million in 2050, an increase of 27 percent…By 2030, more than 20 percent of U.S. residents are projected to be aged 65 and over, compared with 13 percent in 2010 and 9.8 percent in 1970.

The report identifies mortality rates as the driver of trends:

The size and composition of the older population in 2050 will be largely determined by two factors: the size and composition of the population 27 years and over in 2012 and the future course of mortality for that population. While past fertility rates were the main driver shaping the size of these cohorts to date, mortality will influence the pace at which that population declines at the older ages.

…The mortality assumptions for these population projections are guided by past trends and current levels of mortality observed in the United States and in other developed nations. Trends in health-related conditions such as smoking and obesity were also assessed.

Survivorship rates have shown improvement for many decades. In the United States, life expectancy at age 65 was 15.2 years in 1972 and rose to 19.1 years in 2010—a net gain of 3.9 years. The survival gains for those turning 85 have also been impressive. In 1972, the average time to live for someone turning 85 was 5.5 years. By 2010, this had risen to 6.5 years—a net gain of 1 year. Similar trends have been observed in almost all developed nations. For example, life expectancy at age 65 in Sweden increased from 15.7 years in 1972 to 19.8 years in 2010. Life expectancy at age 85 in Sweden increased from 4.9 years in 1972 to 6.2 years in 2010.8

There is a little bit of irony in these trends. On the one hand, you have things like the reduction of smoking that is practically guaranteed to reduce health risks and increase life span in most people. But on the other:

The incidence of obesity increased dramatically between 1980 and 2008, doubling for adults and tripling for children (National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2011)…The direct effect of obesity on survival is less than that for smoking, and there is evidence that the trend is leveling off. The longer-term implications are yet unknown, but could dampen continued improvements in survivorship in future years.

These trends may simply point to the advancements of medicine and technology, but as the above quote points out, the long-term implications of this fairly recent trend are yet unknown. Where is this all leading? As mentioned previously, there are significant implications for Social Security and Medicare, but these are only two examples (although the largest by far) as there are many pension and health care systems throughout the different states and regions of the U.S. There is also the continuous discussion of potential growth in the overall economy. The idea that traditional growth of 4% is not currently realistic (or possible) given the number of workers from the boomer cohort reducing labor participation rates and thus reducing spending, is a common assumption. On the other hand, the very large cohort representing a younger population as well as those in their prime working ages cannot be ignored. While it’s true that availability of workers does not produce jobs, if a number of fundamentals change in the next few years, there could be expansion that we have not seen in years. How might this match off against the implications of an aging population? One thing is certain, in the traditional sense of employment, we have not yet figured out (cumulatively) how to best utilize this large, younger cohort. And we have still not yet adjusted to a post industrial era.